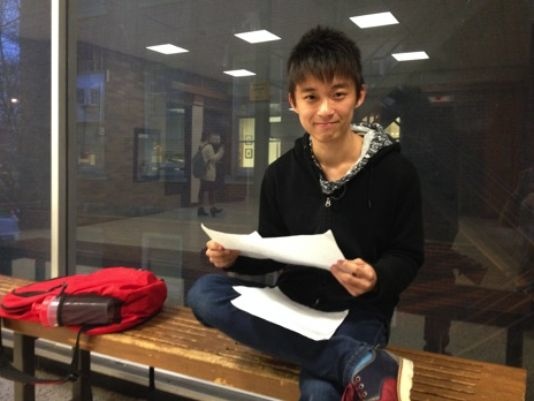

Lin Muyang, a senior from Shenzhen majoring in journalism, says he knows the University of Iowa has tried to help international students integrate into Iowa life but thinks their impact is limited. He says his studies take up a lot of his time. (Photo: Allison Pestotnik/IowaWatch)

By Allison Pestoknik, Iowa Watch

Chinese students at the University of Iowa continue to try making do in a system that isn’t tailored to them, from the admissions process to academics and life on campus, despite moves by the university and others over the past several years to make life more pleasant for them in the United States.

The students remain largely self-segregating and struggling with many aspects of college life, interviews during the fall at UI revealed.

This follows several reports over the past year and a half, including one by IowaWatch, about what is happening and university officials taking a closer look at the problem.

It would be inaccurate to say nothing has been done to improve the situation. Over the last several years, the University of Iowa has increased the number of programs aimed at helping its international students acclimate.

“It’s an ongoing project,” Dean of International Programs Downing Thomas said. “We welcome input from international students.”

A Friends Without Borders program was started in fall 2014 to connect U.S. upperclassmen with incoming international freshmen. Another buddy program is based at the university's Tippie College of Business and matches international and local students as buddies for a semester. Additionally, the Friends of International Students program, a nonprofit organization that is not part of the university, matches international students with Iowa City residents to help them experience local culture.

The university also has started providing some special services for Chinese students, including pre-departure sessions in China for incoming students and broadcasting graduation ceremonies in Mandarin for family members back in China.

The efforts have received mixed reactions from Chinese students who were interviewed.

“The school definitely has more chances for international students,” said Li Nan, a senior from Dalian studying accounting and business. “They make a better diversified environment for us.”

But Yang Canyi, a freshman from Tianjin, said she was unaware of any programs aimed at helping Chinese students.

Lin Muyang, a senior from Shenzhen majoring in journalism, said that although he knows of efforts to help international students, he thinks the impact is limited. He once attended a pumpkin carving event for international students as part of a homework assignment. He said the event was a nice effort on the part of the university but that he usually is too busy with schoolwork to participate in such events.

Li Jiatong, a senior from Jinan, said that she hadn’t noticed any changes in her four years at the university except for “more and more Chinese students.”

“Christians and Chinese are the only kinds of people trying to help Chinese,” Li Jiatong said. “International students need more help than other students. I feel like nobody notices us.”

Enrollment increase

In 2007, there were 568 Chinese students enrolled at the University of Iowa, plus 117 from Taiwan. This fall, there were 2,842, with an additional 72 from Taiwan.

The recent influx of Chinese students is no secret. It has made national news and IowaWatch reported on this in a June 2014 story by Shen Lu that the Society of Professional Journalists named the best online news story written by a college student journalist for that year. So why the increase?

University authorities “want to make money,” Li Nan said.

Iowa residents pay a little more than one-fourth — 29 percent — of what international students pay in tuition and fees, making international students an important source of revenue.

Thomas said the bigger financial picture is that state appropriations have gone down, costs continue to rise and the population of college-age Iowans is not likely to increase significantly.

“We are increasingly relying on out-of-state students ... whether they come from Naperville or Beijing,” Thomas said.

Well over half of the university’s international students are Chinese. That is a reflection of how many potential students in that country of some 1.35 billion people are interested in studying in the United States, especially when China cannot satisfy its own demand for quality higher education, Thomas said. The situation comes down to a case of supply and demand.

Self-imposed segregation

At Shandong University in Jinan, China, international students live in their own campus within a campus. Regulations strictly limited exchanges between international and local students. Chinese students live and study in separate buildings and have a strict 11 p.m. curfew that prevents them from socializing late, even on weekends.

The situation at the University of Iowa doesn’t look much different in some ways, except that Chinese students in Iowa are in the minority and the segregation is almost entirely self-imposed. Chinese students and American students might live in the same residence halls and take the same classes but cross-cultural interactions and friendships remain nearly as limited as in Jinan.

Chinese students usually apply to attend the University of Iowa with the help of agents. Generally agents are third-party companies specializing in overseas college applications, helping to translate and refine documents such as recommendation letters and communicating with colleges on behalf of students. Sometimes agents are also on staff at Chinese schools.

Li Jiatong, University of Iowa senior studying Chinese literature. (Photo: Allison Pestotnik/IowaWatch)

“Many of us use agents to apply for schools because we don’t know the process,” Li Nan said. “When we apply to Chinese college we don’t have personal statements.”

Chinese high school teachers rarely know their students on a personal level, making it hard for them to write genuine letters of recommendation for college. Even if they know their students, their knowledge of English generally is insufficient.

“Chinese teachers don’t speak English. They need people to translate these letters, and during this process things change,” Li Jiatong said.

Third parties step in to fill whatever gaps need to be filled, from flexible translations to beefing up a student’s credentials. Cases of students writing their own recommendation letters also are common.

Thomas said the University of Iowa prefers to deal with students directly. “We tell them they don’t need an agent,” he said. “It risks complicating things.”

The English matter

Language problems go beyond application documents. Chinese students and the university have to deal with whether or not the new students from overseas have a sufficient grasp of English to live and study in the United States.

Thomas said Chinese students in years past have had problems with English but that the situation has improved since the university increased several years ago the required score from TOEFL testing. TOEFL is a standard test for English proficiency required for admission.

But some Chinese students said TOEFL scores do not tell the whole story.

“No matter how high a grade you can get, when you come here you start over,” Li Jiatong said. “If you just prepare for the test, all you know is about the test.”

“English education in China kind of ignores speaking, but speaking is very important,” Lin Muyang said. “A lot of students know what they want to say, but are a little too shy.”

Jia Yuanfang, a senior from Hebei studying business and art, said she has trouble understanding professors because they use words and phrases she doesn’t know. She said this caused her to get a C in a class.

“The professor didn’t provide any textbook or materials, so all the international students did really bad on the test,” Jia said.

Not being comfortable in English also has negative consequences out of the classroom. Yang Canyi said some Chinese students might shy away from talking more to American students. “Maybe they are like me. I think my English is not good,” Yang said.

University of Iowa senior Jia Yuanfang, from Hebei, China and studying business and art, at Food Republic, a downtown Iowa City restaurant, in early December 2015. (Photo: Lin Muyang/IowaWatch)

Beyond language

More than just the language barrier, however, keeps Chinese students largely segregated from their American peers. Rather, the combined force of language and cultural differences play the biggest role, a series of interviews for IowaWatch showed.

“It’s easy and comfortable to hang out with just Chinese students,” said Lin Shuhui, a staffer with University of Iowa International Programs whose job is to help with international student retention. Lin, from China, completed her undergraduate degree at Iowa and knows firsthand what Chinese students face.

“I usually encourage them to get more involved on campus,” she said. “I know students that might have low English but get very involved and then improve really quickly.”

Getting more involved with Americans does not come naturally to many Chinese students. Perhaps this should come as little surprise, considering they come from a country where Facebook, YouTube and occasionally popular American TV shows are banned.

“We’re not in the mainstream society. It’s hard to make friends when they are talking about a drama we don’t know,” Li Jiatong said. “You feel there’s a wall there you can’t break.”

Li Nan said, “There’s two aspects. One is language. The other is if I’m willing to. Sometimes I just don’t want to change a lot.”

Li Nan said she hears from friends back in China who are having an easier time with college than Chinese students she knows in Iowa.

“They’re having more fun,” she said. “The burden is not so serious.”