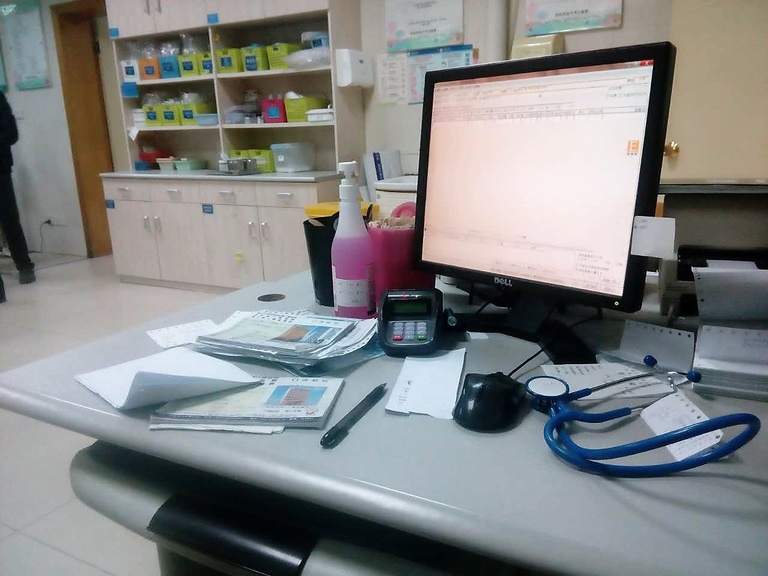

In China, patients still use paper medical booklets (on the left of the desk).

“How will doctors treat me if I fall sick in China?” “How will my medical bills be handled?” “How will I communicate vital information such as allergies to the medical staff if I have an emergency?” These are questions that many foreign students, including me, often forget to consider upon their arrival to China. Unfortunately, many of us realized our mistake only after a medical emergency had already arisen. Being a premedical student, I thought I could start trying to save aspiring globe-trotters’ lives by providing a few tips about the Chinese medical system.

First off, unlike American hospitals, which offer sensibly homogenous levels of performance, Chinese hospitals are divided into three divisions and offer three different levels of care. For students living in China, first-level university campus hospitals mostly deliver primary, acceptable care while third-level teaching hospitals deliver state-of-the-art care. The former is cheaper, but the latter is better. Personally, before understanding that I could ask the University of Iowa students’ CISI insurance company about where to receive the appropriate care depending on my needs, I went to my campus hospital for light issues before submitting my bills directly to the CISI, and I had no problem.

Of course, while debating where (or even whether) to seek care, American students will instinctively wonder how much out-of-pocket money they will be asked for. Most of the time, if UI students open a case file with CISI ahead of time, before going to the hospital or provider, CISI can direct them to the most appropriate hospital and provider (even English-speaking ones), and provide payment directly to the provider. CISI may not always be able to pay every provider up front, so students should always call CISI first for non-emergencies. As a side note, students with an on-going condition who need to continue seeing a doctor while abroad should call CISI ideally before leaving the US, to have them help set up a continuation of care plan. In case of emergency, on the other hand, without a means to call CISI, students should try to be brought to an emergency room previously indicated by CISI. Students will be expected to pay everything out of pocket in cash before receiving care. Only if a student is unconscious or in a life-threatening emergency without cash will the hospital provide the student with care and ask for payment when the situation is resolved. Because hospitals do not accept credit cards nor payment through phone apps such as Alipay, any foreigner should always have at least a couple hundred yuan bills available in case of emergency, especially when traveling. Keeping all medical receipts during an emergency is a must in order to submit them later to CISI. After the emergency, students should contact the insurance company, give them information about the hospital, and open a case file to hopefully secure a guarantee of payment with the hospital. The International Programs 24/7 emergency cell can also be called at any time for assistance (319-530-2540). It is answered by a UI health and safety official who can call CISI for students who need help or are too sick to handle the case alone.

Main entrance of the Zhejiang University Pediatric Hospital’s older section, third-level teaching hospital, also ranked among the best in the nation.

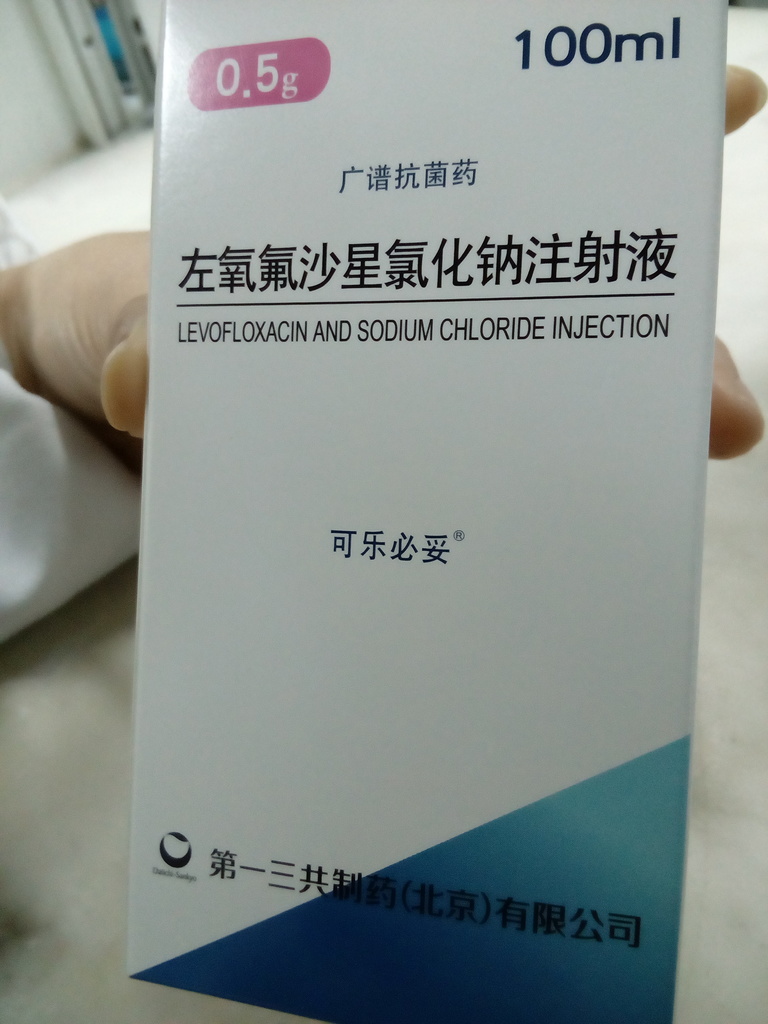

In term of actual costs, though, receiving health care in China is cheaper than in America. For instance, seeing a primary care doctor at a campus hospital may only cost two yuan… or thirty-five American cents (1 US dollar=6 yuan). In third-level hospitals, the cost to see an excellent doctor can go as high as a couple hundred yuan (a couple dozen dollars). Prescribed medication, often a mix of both Chinese and Western medicine, must be purchased at the hospital’s pharmacy after consultation. As a warning to any trypan-phobic students (who fear needles), IV drugs seem to be much more commonly used in China than in America in emergency situations. The cost of multiple treatments can be financially burdening for student. As a rule, foreigners should seek treatment early if they start feeling slightly sick. Never forget that, in China, if a serious infection turns into an emergency leaving no time to call CISI, the patient may have to pay hundreds of dollars upfront and out-of-pocket.

In regular situations, after paying and before seeing a doctor, international students should get prepared to face crowds and lines. Scheduling appointments in China is a rare event, even in specialized departments like dermatology and gynecology. Patients will show up to the hospital; pay for their consultation fee at the registration desk; receive a ticket number and be directed either to the emergency room or another department, depending on their needs; and wait for their turn in line inside the doctor’s office. Yes, inside the office. In China, privacy is an ideology rather than a reality. Why? One, because the odds that two patients will see each other again in a ten-million-inhabitant city like, for instance, Hangzhou, are small, and two, because physicians don’t have time to waste going to get the next patient in a waiting room between consultations.

During some of my shadowing experiences, many doctors explained that they receive too many patients daily to even go to the bathroom or wash their hands during their work day. Many of them even told me they see as many patients in one day as American doctors do in one week. The number of daily consultations (for an eight-hour day) ranged from thirty patients for traditional Chinese medicine doctors to over a hundred for pediatricians. Understandably, having less than five minutes per patient case does not leave them much time for privacy.

Given that the medical staff at hospitals is under strict time constraints, their interactions with patients can be quite impersonal, and even considered rude per American standards. Many foreigners do not cope well with such coldness when they are in pain. Even I, someone who is aware of the hospitals’ atmosphere from having spent time there as a student last summer, was quite shocked when I first experienced a medical consultation as a patient. My advice to international students is to prepare mentally before going to the hospital and keeping in mind the difficulties that medical practitioners face on a daily basis. Because queuing for hours can furthermore aggravate one’s mood, sick international students should always bring a friend (preferably one who speaks Chinese) with them. Non-Chinese-speaking students should translate a list of their allergies in advance to save time and avoid frustrations for both them and the physician.

All in all, being aware that a hospital consultation in China will look nothing like one in America can help students take preventative measures to be ready if and when they fall sick. My main advice regarding health to international students is the following: Pro-actively take care of yourself; always call CISI to know which hospital to visit as soon as suspect symptoms appear; know the care division of the closest hospitals; carry cash on you and keep the receipt of the bills you pay for insurance purposes in

case of an emergency; be compassionate towards medical staff members; and consider your visits to the hospital as cultural experiences. You might learn more than you think with an open mind.

Chinese intravenous version of a common antibiotic also available in pills.

*Astrid Montuclard is a guest blogger studying Chinese and Pre-medicine at the University of Iowa. An international student born in France and raised in Tahiti, she came to the UI to run track. As a Senator for Student Government last year, she spearheaded the new mental health awareness campaign True@TheU, launched this fall on campus.

Student blog entries posted to this International Accents page may not reflect the opinions and recommendations of UI Study Abroad and International Programs. The blog is intended to give students a forum for free expression of thoughts and experiences abroad in a respectful space.