Alba Lara Granero is an Iowa Arts Fellow in Spanish Creative writing program at the University of Iowa. Born and raised in Spain, Alba was aware from childhood of the ways Moroccans were treated. Her childhood friend was teased in school for being Moroccan, leading Alba to wonder about the social reasons behind the cruelty. This question appealed later to her pursuits in social justice and literature, and became the springboard behind her 8 week Stanley Award for International Research project to Spain, where four important historical archives were located for her MFA thesis. The texts, from 1492 to 1650, related to the “morisco issue” – a term coined to refer to all discussion, political or religious, concerning those Muslims who converted to Christianity. Although the particular era is believed to be one of tolerance, her personal experiences and research show how moriscos were never truly accepted in Imperial Spain. Read on for more about her travels and research discoveries.

The beautiful Alhambra, meaning 'the red one' in Arabic, is a complex of Islamic palaces built between the 9th and the 14th centuries in Granada.

By Alba Lara Granero

It was impossible to get lost. The address of the archives was clear on the website: monumental area, next to the cathedral. It was not my first time in Cuenca, but I did not know how long it would take me walking from downtown, where my hostel was. I left two hours before the archives opened to make sure I would take full advantage of the four hours a day the archive is open.By Alba Lara Granero

The Eyes of the Moor look at Cuenca since the 17th century

I got to the area in twenty minutes but could not find the archive. There was nobody around that early in the morning, so I walked up and down the street where it was supposed to be several times.

Perplexed, I stopped at a balcony in uptown where there is a magnificent scenic lookout. It was beautiful and peaceful, all mine, and a street-sweeper approached me and started talking to me. I told him that I was in Cuenca because I was working on a literary project about the Moriscos (Muslims that were forced to convert to Christianity in Early Modern Spain), and that I could not find the archives.

He told me not to worry, that it was near, and he would go with me up to the door. He mentioned that if I had time he would show me something that might be interesting to me. One street away, he pointed out to a point in the mountains. From there I could see the eyes of the Moor: a landmark to illustrate a romantic legend based on the rivalry between the two religions back the day.

I worked hard for the two weeks that I was in Cuenca. The archives are so rich and well conserved that I found dozens of inquisition trials. Given the amount of materials they store, it would not have been possible to read everything in just a couple of weeks, but the staff was extremely helpful and allowed me to take pictures of the trials I was interested in but could not read.

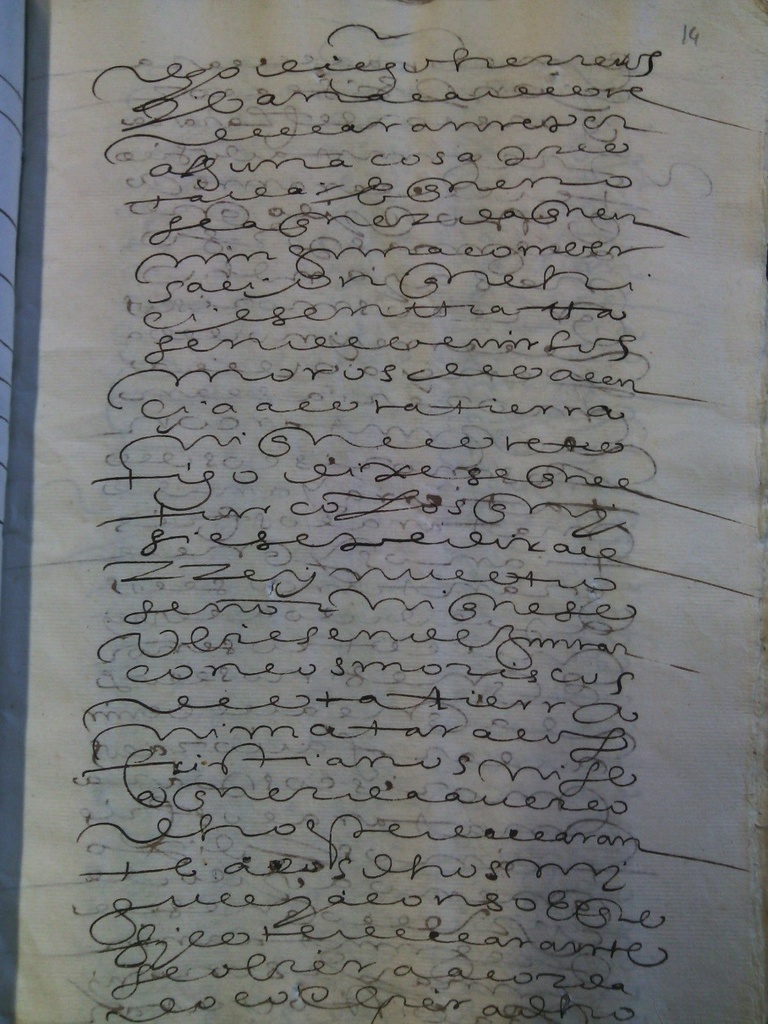

The result: almost nine thousands photos (a photo per page) that will keep me busy for several months. In Madrid I consulted two other archives and spent hours trying to decipher what was written in the texts from the 16th and 17th centuries.

Sometimes it was not easy, but I learned that it required practice, and, when I was not in the archive, I devoted myself to the study of paleography in order to better write down the trials I was reading (although the staff was extremely nice in Madrid too, it was forbidden to take pictures).

Sometimes the manuscripts were hard to read.

That is how I learned about the Alegría’s family, for instance. I read a series of interconnected trials that narrated the tragedy of the family from the town of Bolaños. Accused of being Moriscos, they tried to run away to another village and avoid the Inquisition’s punishment.

Most members of the family were interrogated for long hours and their versions did not coincide. The inquisitors asked over and over in order to get the only answer they were looking for: a confession. To my project this is not only useful because of the story and the characters, which I will use, but also for the dramatic tension that one can find in the inquisition trials.

For example, the matriarch of the family, Catalina de Alegría, an older woman, tried first to avoid the interrogation. She used a much extended tactic: making excuses. Headaches, alleged losses of memory and other complaints allowed her to evade bits of the interviews.

She defended the quality of ‘good Christians’ of all her family and denied that they celebrated Muslim rituals or ate pork. But the pressure of the inquisition was high and, after some interrogations, she acknowledged that she was secretly ‘Morisca.'

Inquisition’s notaries weren’t allowed to write down their impressions about what the culprit might feel, but recorded when the accused were crying, begging, as well as every word uttered in the courtroom.

The prisoner would even ratify that the report agreed to his words. This is another great hint to my work: the colorful and life-like language.This was not enough for the inquisitors though, and, at this point, they decided to “darle tormento” (torture her) until she recognized that everybody in her house took part in the Islamic rituals. A reader of the manuscript can easily feel the progression of the trial, the silences, and the fears.

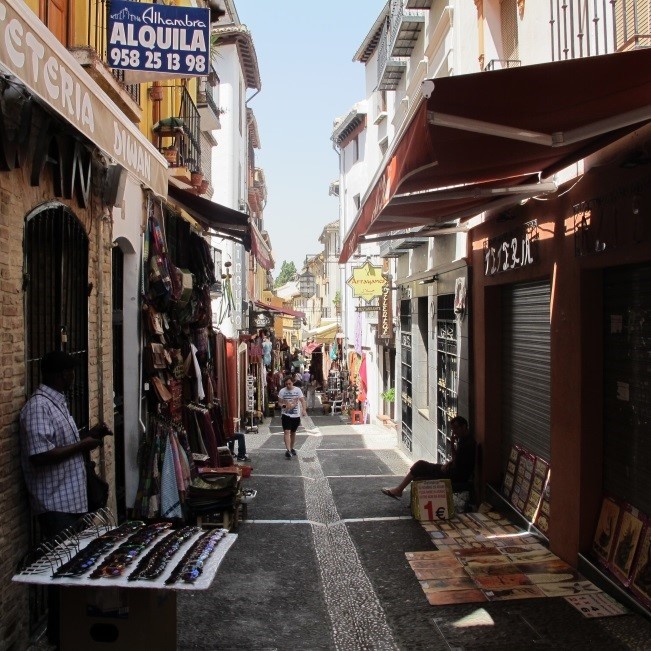

But my trip didn’t end at the archives. Thanks to the Stanley Graduate Award I was able to visit Granada and got to know firsthand the city from which Spanish Moriscos were first expelled in 1571.

Granada is, even nowadays, a symbol of the long coexistence between Moors and Christians. In fact, Granada’s most famous monument is the beautiful Alhambra. In this last part of my research, I got a better understanding of the Moriscos’ everyday life and suffering that will be translated into a more accurate recreation of the setting in my writing.

La Alpujarra, a mountain area where the Moriscos hid for three years during the war, is a magical place full with stories about legendary rivalries between Moriscos and old Christians.

I have collected interesting, astounding and new materials for my book. We might say that phase one is completed even if I continue reading about the Moriscos’ conflict. Now it’s time to put all the writing and sketches in order and try my best to write my book, which would serve as my Master’s thesis from the MFA in Spanish Creative Writing in Spring 2016.

No more sad legends about this: let the eyes of the moor gleam with joy. Before that, I will read an excerpt of my creative writing at the Stanley Speakeasy event and will send it to some magazines to try to get it published. I will love to share these stories with my colleagues and be glad to receive their suggestions.

From all I have read, seen, and heard, I know that similarities between people are more powerful than their differences, and I would love to write my stories to emphasize what unites people.

Find out more about the Stanley Graduate and Stanley Undergraduate Awards for International Research, funded in part by the Stanley-UI Foundation Support Organization.